The Software of Abundance

Part 2 of the Baumol-Veblen Entanglement

Remember the dotcom bubble? I literally had a stranger knocking at our office door after hours offering to invest, no questions asked.

It is Fall ‘99. My second startup, ShoppingList, just closed another round — tens of millions of dollars. We were dismissing nine-figure acquisition offers. Stealth mode. Big team. Board-approved plans. We are partying... well, it was Y2K.

Within 12 months, I was laying off everyone — 60 hard-fought employees who had trusted me with their careers. I was literally in tears.

I’d done everything the “right” way. No one beat a path to my door.

It took me years to understand what happened — not just what went wrong, but why. Part 1 of this series described what I’ve called the Baumol-Veblen entanglement: education, healthcare, and housing keep getting more expensive partly because they’re genuinely hard to make cheaper, and partly because they’ve become status symbols. The two problems are tangled together, and we keep trying to fix one while ignoring the other.

Part 2 is about what untangling might look like. I don’t have a policy platform. What I have is a hunch, and some things I’ve seen.

The Invisibility Cloak

Here’s the thing about status competition: nobody calls it that.

I have a friend who voted for Trump. When I actually listened to him — I mean really listened, not the kind of listening where you’re quietly preparing your rebuttal — his grievance wasn’t what I expected. The game felt rigged, he said. The essays, the zip codes, the invisible gatekeeping. He wasn’t wrong about the rigging. He was wrong about who was doing it.

Meanwhile, my Palo Alto progressive neighbors fight to protect “neighborhood character.” I sit in these meetings sometimes. The language is all about trees and setbacks and historical preservation. But what it means is: protect the scarcity that makes our houses worth what we paid.

The grievance is real. The game causing it is invisible.

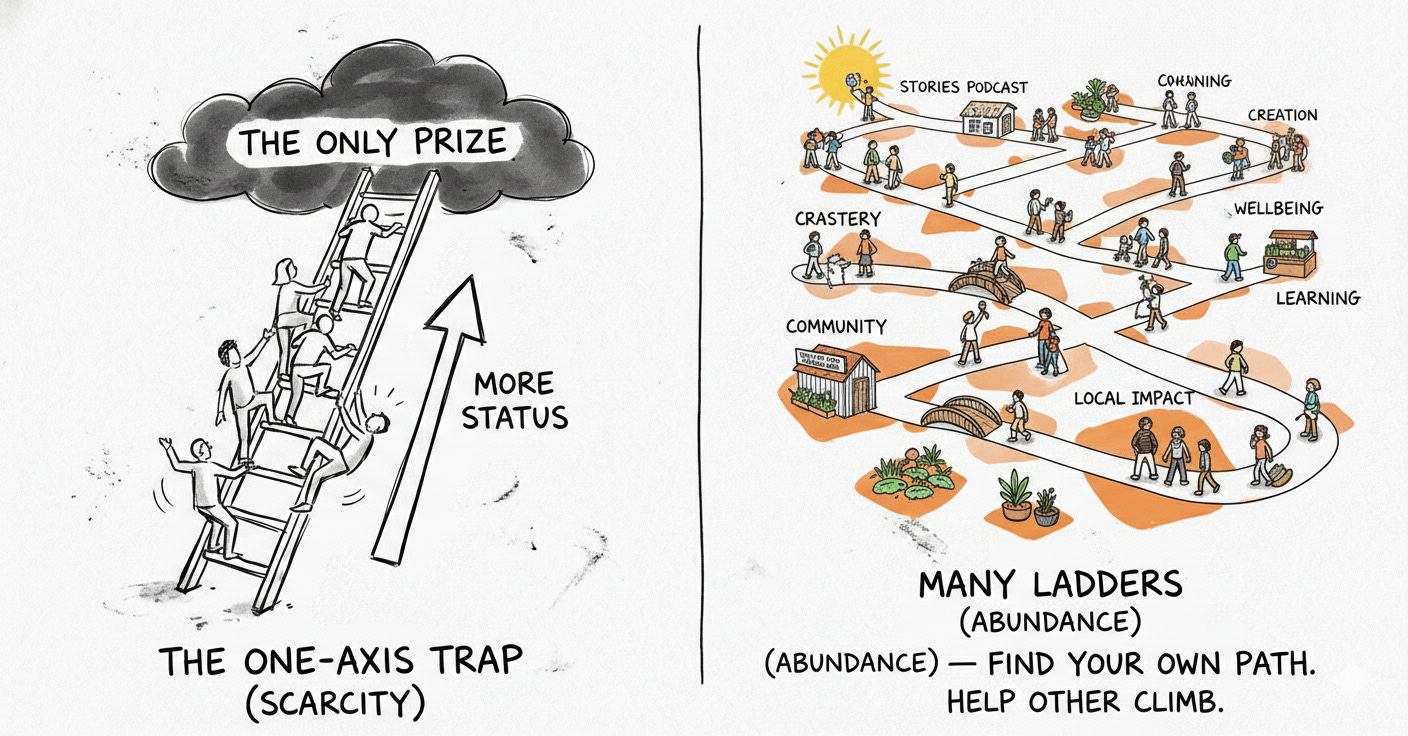

We argue about DEI, immigration, housing — always the symptoms. The underlying disease is that we’re all fighting over spots on a ladder that everyone agreed was the only ladder worth climbing. And nobody wants to say that out loud, because then you’d have to ask: why is there only one ladder?

The One-Axis Trap

Which brings me to something I saw last year that I keep thinking about.

I was at Edge Esmeralda 2025 — a pop-up village in Healdsburg where technologists, artists, builders, and assorted weirdos live together for a month, trying to figure out what new forms of community might look like. It’s hard to categorize, which is sort of the point.

Audrey Tang, Taiwan’s former Digital Minister, was speaking. She described experiments they’d run mapping public opinion in multiple dimensions instead of yes/no votes. When you do that, she said, hidden coalitions appear. People who seem like enemies on one issue turn out to be allies on another.

It stuck with me because it named something I’d been feeling. We’ve collapsed every disagreement onto a single axis. Left or right. Red or blue. Elite or populist. You pick a side, and suddenly you’re supposed to have the same position on immigration, housing, healthcare, education, and what counts as a good life. That’s not how anyone actually thinks. The all-or-nothing alignment isn’t real — it’s what happens when you only ask one question at a time.

The Software Problem

There’s a movement building around abundance — Ezra Klein and Derek Thompson have written about it, AI is accelerating it. Build more housing. Fix permitting. Make education and healthcare cheaper through technology. I believe in all of it. That’s the hardware.

But I keep coming back to a nagging question: what if we build all that abundance and the same status games just eat it?

Because that’s what happens. Give people better tools without changing the game and you just get a faster treadmill. AI-optimized applications for the same 2,000 Harvard slots. Shinier rungs on the same ladder.

You can tell people to stop competing for the same few prizes. But that’s like telling someone to relax. It doesn’t work unless the conditions change.

So what are the conditions? What’s the software?

I think it’s three things: tools that let ordinary people build things that used to require specialists. Communities that say “your weird small idea counts.” And people around you who pay attention to what you’re trying to do — who spot the openings you can’t see alone.

I think I caught a glimpse of all three working together.

What I Built Instead

After ShoppingList crashed, I tried something different. Smaller. Quieter.

Small ideas, doable in weeks. Distribution baked into the product. Thread Reader — a tool for unrolling Twitter threads — spreads because every unroll request is public by design. Every user interaction is a billboard, not a gate.

VCs call these “lifestyle businesses.” Dismissively. But it’s been running for years, serving millions, compounding in a direction that matters to me. A different ladder. One I built instead of climbed.

But the examples that really shook something loose weren’t my own.

A Room Full of Clicks

Last year I joined Will Mannon and Dan Sleeman’s Act 2 — a cohort for people looking to build something new. I was a student, but I also helped Louie Bacaj teach the vibe-coding track. In practice, that meant I spent a lot of time on the floor helping fellow students get Claude Code installed on their machines, showing them tools like Lovable and Replit, and being the all-around support guy for anyone who wanted to build something or just talk through an idea.

At the start of the course, nobody had a great idea. That’s not a flaw in the program. That’s the point.

A fellow student named Cris Valerio was musing about doing a local main-street business. She couldn’t quite articulate why that called to her. Something about wanting to build something real, something rooted. She didn’t arrive with a plan. She arrived with a pull.

Then she started building. Vibe-coding — using AI tools to create software without being a developer. And through the act of making things, a memory surfaced: those bleary 3 AM feedings with her own kids. Wishing someone had been there. The need she’d lived through collided with tools that could finally do something about it.

By the end of the cohort, she’d built Tahoe Night Nanny — a live marketplace connecting new mothers with night nurses. Not a pitch deck. A working product, born from a real problem she’d carried for years without knowing it was a project.

Kyle McGovern’s story cuts differently. He had wanted to interview elderly people and preserve their stories on YouTube for seven years. Seven years of believing in the idea and not being able to act on it — not because he lacked tools or talent, but because he didn’t know where to find guests. He felt lost.

When Kyle joined Act 2, he met a fellow student named Sandra. A couple days later, Sandra saw a flyer at a library from a 95-year-old piano teacher. She took a photo and texted Kyle: “Hit him up. He could be a great guest!”

That was it. That was the whole unlock. Seven years of waiting, broken because someone in his community noticed an opportunity he couldn’t see alone. Kyle booked his first interview. Then his second. He’s now published eight videos and delivered a speech at Stanford about his project.

Nobody in that room was trying to build the next big thing. Cris was building a night nurse marketplace in Tahoe. Kyle was interviewing old people. And I was on the floor helping someone debug an install.

I want to name what I think happened here, because I’ve been watching for it for years and I still almost missed it.

In startup parlance, the holy grail is “product-market fit” — the moment you discover that what you’re building is what people want. But there’s something that has to happen before that, something more personal. I call it the click: the moment a project stops being something you’re exploring and becomes something you can’t let go of. The problem becomes yours — not because someone assigned it or a market report validated it, but because you lived it and it won’t leave you alone.

You don’t arrive at the click by thinking about it. You stumble into it by doing things. Cris didn’t sit down and brainstorm her passion. The act of vibe-coding, inspired by the memory of those 3 AM feedings, turned a wish into reality. Kyle didn’t need a new insight. He needed Sandra to see a flyer.

Two different paths. Cris’s unlock was tools — vibe-coding closed the gap between an idea she’d carried and a product she could ship. Kyle’s unlock was community — someone paying attention to his weird project and spotting an opening he’d missed for seven years. But the underlying condition was the same: you can’t get there alone, and the room matters as much as the tools.

It hit me later that I’d been watching Kevin Kelly’s essay walk around on two legs. In 2008, Kelly wrote “1000 True Fans” — arguing you don’t need millions of customers to have a creative life. You need a thousand people who really care. Beautiful idea. But in 2008 it was mostly aspirational, because the tools to go from idea to product were expensive and hard and the communities to support weird small projects barely existed.

What changed wasn’t the aspiration. The tools caught up — Cris can go from musing to a live marketplace in weeks without becoming a developer. And the communities caught up too — places like Act 2 that say: tahoenightnanny.com counts. Interviewing seniors counts. Your small, weird, local thing is worth doing.

What changed for Cris wasn’t her mindset. It was her situation. A room where her idea made sense to people, tools that let her build it, and someone to help when the install broke. What changed for Kyle wasn’t his dream — he’d had that for seven years. It was Sandra.

That’s not just optimism. That’s the software of abundance.

The Hunch

I don’t have a ten-point plan. I’m not running for anything.

The abundance agenda is right about hardware. Build it all. But we also need new software — communities that say “this counts” about things the old system would dismiss, tools that close the gap between wanting and shipping, and maybe just someone to help you get past the install screen. Or someone to see the flyer you’d never see.

Is this a plan? No. It’s a hypothesis at best.

But I watched Cris go from musing to shipping. I watched Kyle break seven years of waiting because Sandra texted him a photo. And I’ve watched a handful of students, year after year, stumble into problems that grabbed them and wouldn’t let go.

I’m going to keep asking them about the click. Not just about metrics or traction — about the moment it flipped. I suspect the answer will teach me more than anything I could tell them.

There are days when I recollect wistfully about the go-go dotcom days, when I believed I could build the Next Big Thing from merely a brilliant idea, strong ambition, and millions of other people’s money. Then that familiar uneasiness seeps back — the anguish of disappointing so many.

In a blink, I’m brought back to reality.

The next big thing is a trap. The next small thing is a journey.

P.S. I swear I’m not being paid , but both Edge Esmeralda 2026 (Healdsburg, May 30 – June 27) and Act 2 have events coming soon. I'm planning to attend both. Here’s to more Schelling points. Tell me yours below!