The Two Elephant Dance

Baumol, Veblen, and the cost of everything

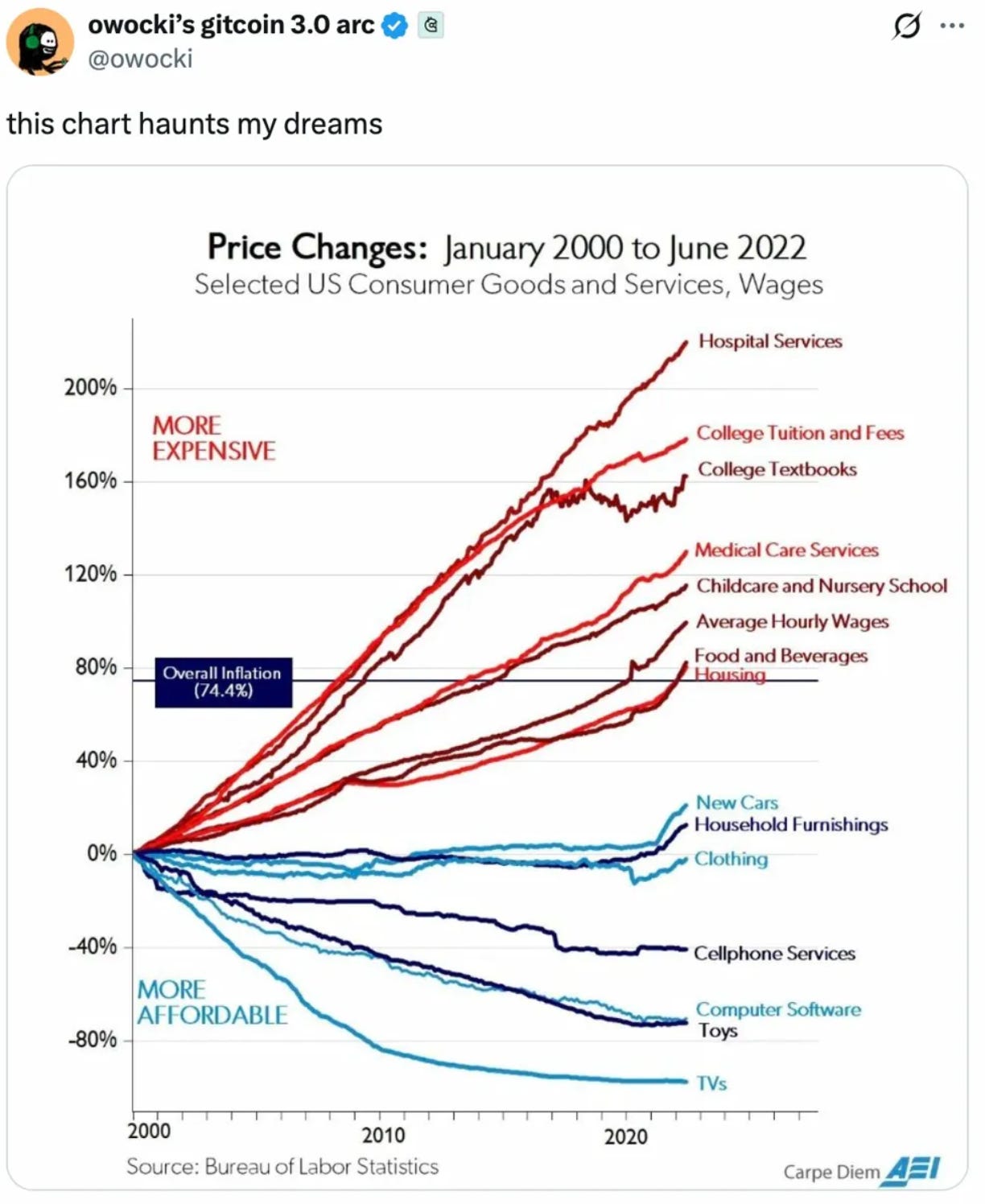

If you doom scroll as much as I do, you’ve probably seen this chart.

It haunts me too. The chart shows something I can’t unsee: since 2000, the things you need — hospital services, college tuition, childcare, housing — have exploded in price. Meanwhile, the things you want — TVs, software, toys, clothing — have gotten cheaper. The essentials eat your paycheck while the gadgets pile up in your Temu cart.

There are two elephants in the room — two forces that explain this chart. One everybody talks about. One almost nobody does. And they’re dancing together in a way, feeding each other in a Moloch trap. Until we see both elephants clearly, we’ll keep proposing solutions that don’t solve the problem.

The Three-Headed Hydra

Look at those red lines climbing relentlessly. They’re not random. They represent the three things you need to build a middle-class life: education, healthcare, and housing.

This is the three-headed hydra eating the American dream. Everything else — your TV, your phone, your clothes — has gotten remarkably cheap. But the three things that determine whether you can raise a family, stay healthy, and have a roof over your head? Those keep slipping further away.

Why these three? There’s a standard answer economists have been telling us for decades. And there’s another answer that almost nobody talks about.

The Baumol Explanation (The Half Everyone Knows)

The standard story is called Baumol’s cost disease. The logic is elegant: some industries get more productive over time, some don’t. A factory that made 100 widgets per worker in 1960 might make 10,000 today. But a nurse can only care for so many patients. A teacher can only teach so many students.

When productive sectors bid up wages, labor-intensive sectors have to match them — even though their output per worker hasn’t changed. Services that require human attention get relentlessly more expensive relative to goods that can be automated.

Baumol explains education (you can’t automate a seminar), healthcare (surgery requires surgeons), and housing (construction is labor-intensive). Layer on the regulation story — zoning, environmental review, occupational licensing, NIMBYs — and the cost disease compounds.

This is all true. If this were the whole story, the solutions would be straightforward: automate what you can, cut the red tape, build more, train more workers.

But here’s what’s been nagging at me: Baumol explains why these services are expensive. It doesn’t fully explain why they feel so impossibly explosive. Something else is going on.

The Veblen Problem (The Half Nobody Talks About)

I started thinking about this differently after a conversation with my neighbor.

He drives a McLaren — the kind of car that costs over a million dollars. He’s on a waitlist to upgrade to the $2 million model. The waitlist is so long, he told me, that when he finally gets it, he can instantly resell and make a million dollars profit.

I kept thinking about what that means. The car isn’t worth $2 million because it costs $2 million to make. It’s worth $2 million because other people can’t have it. The scarcity is the product. And the “profit” my neighbor expects to make? That’s not value creation. That’s pure positional extraction — money transferred from someone even further down the waitlist who wants the status even more.

By standard productivity measures, McLaren looks incredibly productive. Revenue per worker: astronomical. But they’re not creating more utility. They’re manufacturing scarcity and harvesting status premium.

This is a Veblen good — named after Thorstein Veblen, the eccentric Norwegian-American economist who published The Theory of the Leisure Class in 1899. Veblen goods violate normal economic logic: the higher the price, the more you want it. A Rolex isn’t just a watch — it’s a signal that you can afford a Rolex. If Rolexes cost $50, no one would want them.

Here’s what we don’t talk about enough: the three-headed hydra — education, healthcare, housing — all have a massive Veblen component. And it’s entangled with the Baumol component in ways that make the problem much harder than the standard story suggests.

The Hydra, Re-Examined

Let me look at the same three sectors through fresh eyes.

EDUCATION

The Baumol story: Professors cost money. You can’t automate a classroom. Education is labor-intensive.

The Veblen story: Harvard admits about 2,000 freshmen per year. They could admit more. They could offer unlimited online enrollment. They don’t — because exclusivity is the product.

Harvard’s value isn’t primarily the education. It’s the credential, the signal, the scarcity. If everyone had a Harvard degree, no one would want one.

This cascades down. The frenzy over elite college admissions isn’t about learning calculus — any competent school can teach calculus. It’s about position. The “right” preschool leads to the “right” elementary school leads to the “right” college leads to the “right” life. Parents aren’t buying education; they’re buying slots in a tournament.

I have a friend — Chinese-American, incredibly driven — who went from chanting “defund the police” in 2020 to full MAGA by 2024. What flipped him? DEI. Specifically, his perception that elite college admissions were rigged against his kid. His grievance is real: he sees his child grinding through AP classes and test prep, watching the goalposts move.

But here’s the thing: even if admissions were perfectly “fair” by his definition, there would still be only 2,000 slots. The scarcity is the product. We’re all fighting viciously over positional goods while pretending we’re fighting about fairness.

HEALTHCARE

The Baumol story: Doctors cost money. Surgery requires surgeons. You can’t offshore an appendectomy.

The Veblen story: “The best” hospitals, “the top” doctors, concierge medicine, boutique practices — these are status goods. People pay premiums that have nothing to do with outcomes. Being treated at the Mayo Clinic or Mass General signals something about who you are, independent of whether you get better care.

The healthcare system is riddled with positional competition. The “best” pediatrician, the “top” specialist, the hospital with the prestige. Some of this correlates with quality. Much of it is pure signal.

HOUSING

The Baumol story: Construction is labor-intensive. Materials cost money. Permitting takes time. Regulations add friction.

The Veblen story: Mark Zuckerberg’s Palo Alto home is a street and a creek away from East Palo Alto. The property value difference? Probably 10x or more. The physical structures aren’t 10x different. The schools aren’t 10x better. The air isn’t 10x cleaner. The proximity to jobs is identical — it’s the same neighborhood, separated by a creek.

What costs 10x more? The address. The signal. The line on a map that says “Palo Alto” instead of “East Palo Alto.”

And it’s no accident that to the west of Palo Alto sits Stanford — the university that literally birthed the town, that created Silicon Valley, that mints the credentials which justify the housing prices which fund the schools which feed back into Stanford admissions. And Stanford Hospital? One of the most sought-after medical centers in the world.

Education, housing, healthcare — the three-headed hydra isn’t three separate problems. In Palo Alto, you can see it’s one creature, feeding on itself. The trifecta, complete.

And the contagion spreads. Even East Palo Alto — the “affordable” side of the creek — now has million-dollar homes. That’s the Veblen ratchet: proximity to status is itself a positional good.

This is a positional good in its purest form. It’s not just a place to live — it’s a signal that says: I made it. I’m in the club. My kids will be around other kids whose parents made it. The scarcity is doing work for the people already there.

I watch my Bay Area neighbors bid up houses not because the construction is exceptional, but because of what the address means. The NIMBYs fighting new development aren’t just protecting their views — they’re protecting their positional advantage. Every new house dilutes the exclusivity.

The Veblen component isn’t equally strong in all three heads. Housing in Palo Alto is drenched in it. Education sits in the middle — the learning is real, but the credential does heavy lifting. Healthcare is the weakest case — you go to the nearest ER when you break your leg, not the one with the best brand. But the prestige tiers exist in all three. The mix varies; the dynamic is present.

The Entanglement

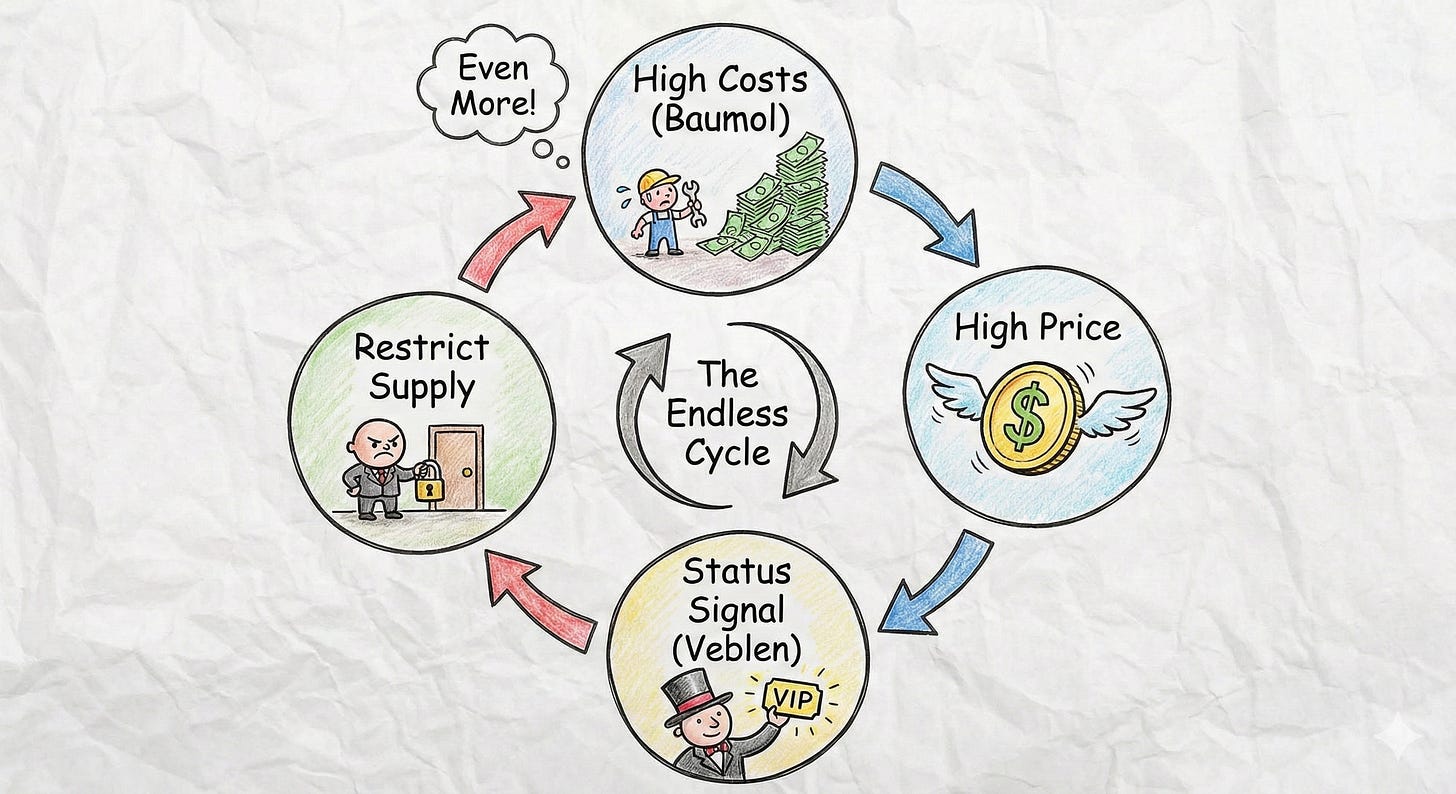

Here’s what makes this genuinely hard: you can’t cleanly separate Baumol from Veblen. They’re not just mixed together — they feed each other.

Take college tuition. How much of that 180% increase is Baumol (professors cost more, campuses need maintenance) and how much is Veblen (schools competing on prestige, climbing walls, fancy dorms, administrative bloat driven by rankings)?

The honest answer: we don’t know. But it’s worse than that. The two dynamics are reflexive — each one amplifies the other.

Baumol makes education expensive → expensive becomes a signal of quality → schools compete on price as a status marker → tuition rises beyond what Baumol alone would predict → the high price becomes the product → which requires more administrators and amenities to justify → which feeds back into Baumol costs.

The same loop runs in housing. Construction costs rise (Baumol) → housing gets expensive → expensive neighborhoods become status markers (Veblen) → residents fight to restrict supply to protect their status investment → restricted supply drives prices up further → which attracts more status-seeking buyers → which justifies more restrictions. The dance goes on.

And healthcare. Labor costs rise (Baumol) → healthcare gets expensive → expensive care becomes a signal of quality (Veblen) → providers compete on prestige rather than outcomes → prestige requires more specialists, more equipment, more marble lobbies → which drives Baumol costs higher → which makes the status signal stronger.

It’s not Baumol plus Veblen. It’s Baumol times Veblen — a multiplicative spiral where each dynamic reinforces the other.

We talk as if it’s 90% Baumol and 10% other. But what if the interaction effect is larger than either component alone? What if the real driver is the feedback loop between them?

We’d be trying to engineer our way out of a problem that’s fundamentally about human psychology and social competition — while our engineering solutions get absorbed into the status game and make it worse.

The Policy Trap

This leads to a predictable policy failure — one that transcends party lines: restrict supply, then subsidize demand.

Student loans make college “affordable” — while tuition skyrockets. Housing vouchers help renters — while NIMBYs block construction. Healthcare subsidies expand coverage — while costs spiral. The pattern repeats everywhere.

And both parties play the same game. Governor Newsom sends $18 billion in “inflation relief” checks to Californians — the same California where zoning laws make it nearly impossible to build housing. President Trump directs Fannie Mae and Freddie Mac to buy $200 billion in mortgage bonds to lower rates — while tariffs raise construction costs. Lower rates mean more demand chasing the same constrained supply. The check gets cashed; the prices go up; the next election demands another check.

If the problem were purely Baumol, demand subsidies might eventually create pressure to expand supply. More students can pay, so maybe schools expand capacity.

But when you subsidize demand for a Veblen good, you’re not helping people afford the thing. You’re funding the positional arms race. More money chasing the same 2,000 Harvard slots. More money chasing the same “good school district.” The prices rise, the exclusivity is preserved, and the subsidy becomes a transfer to whoever controls the scarce supply.

And they have every incentive to keep it scarce.

The cycle is almost comedic: prices go up, people get angry, politicians subsidize demand, prices go up more, people get angrier, politicians subsidize demand more. Everyone knows it’s just a temporary relief. But confronting the supply side — the Baumol regulations and the Veblen status game — is politically harder than writing another check.

The AI Question

This brings us to the present moment. AI is the most significant technological change since the internet, maybe since electricity. Techno-optimists promise it will finally solve Baumol’s cost disease — automating services that have resisted automation for decades.

I listened to Marc Andreessen on a podcast recently, making the case that if AI really works, “productivity skyrockets and prices collapse.” This sounds compelling until you think about it for five minutes.

AI tutors, AI diagnostics, AI legal services — yes, these could genuinely reduce the labor intensity of services that have been stubbornly expensive. The Baumol part might actually get solved.

But here’s the question nobody’s asking: what happens to the Veblen component?

If AI makes basic education effectively free, does that reduce the cost of education? Or does it just intensify the positional competition for whatever education AI can’t provide — the elite institutions, the human-taught seminars, the credentials that signal “I didn’t need the AI”?

If AI makes basic healthcare abundant, do we all get healthier? Or does the positional competition migrate to “premium” care, human doctors, boutique medicine that signals you can afford to not use the AI?

Here’s a chilling thought that hit me as I was writing this: perhaps the reason AI won’t destroy all our jobs is itself a Veblen phenomenon. Jobs might survive not because humans are needed, but because human labor becomes a status signal.

“Handmade.” “Artisanal.” “Human-taught.” “Seen by a real doctor.” The scarcity of human attention becomes the new luxury good. The AI can write the legal brief, but you hire the human lawyer because you can afford to. Work becomes a performance of status rather than a source of value.

This isn’t comforting. It means jobs are “saved” but hollowed out. It means AI abundance for the masses, human service for the elite. The Veblen ratchet tightens.

My worry is this: AI might solve Baumol while accelerating Veblen. We’d get massive productivity gains that show up in the statistics, while people feel just as squeezed — because the status competition has shifted to new terrain.

The treadmill doesn’t stop. It just gets faster.

So Now What?

I’ve laid out the diagnosis: the three-headed hydra of education, healthcare, and housing isn’t just a Baumol problem (services are hard to automate) or a regulation problem (we’ve made it hard to build). It’s also a Veblen problem (we’re competing for position, and scarcity is the product). The two dynamics are entangled, reflexive, and our policy interventions keep making it worse.

But diagnosis isn’t cure. And here’s where it gets uncomfortable.

The Veblen problem implicates us. Not just “the system” or “the elites” or “the regulators” — us. The homeowner fighting new development. The parent clawing for the “right” school. The patient demanding the “best” hospital. We’re all playing the game, often without seeing it.

I live in Palo Alto. I see the trifecta every day — Stanford, Stanford Hospital, the houses across the creek from East Palo Alto that cost ten times as much for reasons that have nothing to do with the physical structures. My neighbors and I have bid up these prices. That’s what makes this hard to write about.

Ezra Klein and Derek Thompson’s Abundance movement is right that we need to build more. But abundance alone won’t solve a problem that’s partly about human nature — our deep need for status, for position, for being ahead.

What would it mean to actually see the Veblen dynamic clearly? To name it in our politics, our policies, our own choices? To decouple status competition from the essentials of a decent life?

That’s where this gets political. And that’s Part 2.

Next: The politics of positional scarcity — why we fight about DEI instead of Harvard’s 2,000 slots, why blue states are “failing” at success, and what a politics that takes Veblen seriously might look like.

If you’ve ideas what should be in Part 2, please drop a line!

This is really, REALLY interesting, Chao. Your examination of the three-headed hydra takes on a very complex problem in a way that's understandable for everyone.

By the way, I drive a 2003 Toyota Matrix that is destined to become a classic within a few years. If your friend wants to swap his $1 million McLaren straight across, I'm willing to listen. Thank you in advance for connecting us!

This is really interesting Chao and I appreciate you laying it all out. It is an interesting phenomenal and feels hopeless in some ways. I’ll add to the problem in these sectors is labor supply. More and more, the smart people who may have had an interest in becoming teachers and healthcare workers see that their counterparts make more money and have less student debt after college. Why go $400k in debt and wait to work fully as a doctor until you’re 30 when instead you could get a cushy tech job (even more accessible because of AI) instead? The supply of people willing to do these jobs in these industries is going down. And to your point about healthcare, it’s a very different experience to go to a low income clinics in San Jose than to Stanford. The care is as good but the staff is swamped. Getting a referral is impossible. This will only get worse.

That all being said, I do feel like this problem was much worse for me when I was in the Bay Area vs the rest of the country. High cost of living cities where the wealth inequality is huge are feeling the effects of this way more.

Looking forward to your next essay!