The Wrong Flywheel

The Network State, Three Years Later

An update to my 2022 review of Balaji Srinivasan’s The Network State

The Promise

In September 2022, I wrote a review of Balaji Srinivasan’s The Network State. The book was a breath of fresh air. I was delighted he presented a one-sentence, one-page and then one-book version of his thesis. I loved how he stressed that the book was a work in progress—a living document, published online, that he’d keep updating like a startup iterating toward product-market fit. Alan Kay said “the Mac is the first personal computer good enough to be criticized.” That’s the spirit in which I offered my critique.

My main concerns were:

Skeuomorphic thinking: The book was too constrained by the nation-state paradigm it claimed to transcend—like introducing the iPhone by spending most of your keynote on Alexander Graham Bell’s telephone.

The missed plurality insight: A digital book can reside in many bookshelves simultaneously. Similarly, I could belong to multiple network states at once. This is a fundamental difference from nation-states, where 99% of humanity is tied to one country for life. I wished Balaji had focused more on this crucial difference.

The “what problem does this solve?” question: The book described what was wrong with the world and how network states were different, but very little about how they would actually solve the problems we face.

The One Commandment tension: In a world of easy exits and multiple memberships, would a single unifying moral premise still hold? What happens when your commandments conflict and you’re a citizen of both communities?

To his credit, Balaji reached out after the review. “Good feedback,” he wrote. “Addressing most of that in the v2.”

I was genuinely excited for v2.

The Drift

Three years later, v2 never arrived. The online book remains largely unchanged since 2022—so much for iterating toward product-market fit. But Balaji’s public vision evolved dramatically.

In September 2023, Balaji gave a four-hour podcast interview that revealed a different vision. He called for tech-friendly people to seize political power and take control of cities. Democrats would be excluded from areas the “Grays” (his term for the tech tribe) control. He suggested cultivating police loyalty through “policeman’s banquets” and jobs for their relatives—finding officers who would enforce laws favorable to tech interests.

“No Blues should be welcomed there,” he said, comparing his color-coded system to Bloods versus Crips.

This wasn’t the network state vision of 2022. That vision promised escape from tired political binaries, communities organized around shared purposes rather than tribal resentments. What emerged was... tribal resentment with blockchain aesthetics.

By August 2024, Balaji announced the Network School, a physical campus in Malaysia. The ideological requirements for admission:

“The Network School is for people who admire Western values, but who also recognize that Asia is in ascendance, and that the next world order is more properly centered around the Internet — around neutral code — than around either declining Western institutions or a rising Chinese state.”

There’s a genuine attempt at a third way here—not captured by the US/China binary, centered on “neutral code.” I actually like this sentence. The 2022 Balaji is still in it.

But then come the specific requirements:

“For those who understand that Bitcoin succeeds the Federal Reserve, that encryption is the only true protection against unreasonable search and seizure, that AI can deliver better opinions than any Delaware magistrate.”

Read that again. Not “explore whether” or “investigate how”—but “understand that.” These aren’t questions. They’re answers. Catechism, not inquiry.

The vision was right there — “neutral code” transcending both declining Western institutions and a rising Chinese state. And then it was immediately contradicted by a list of specific policy positions dressed up as admission criteria. The gesture is pluralist. The implementation is partisan. That gap is the whole story of what happened to the Network State.

The Visit

I decided to see for myself.

The Network School is located in Forest City, Malaysia—though the marketing describes it as “a beautiful island near Singapore.” The distinction matters. Singapore signals first-world efficiency, rule of law, Lee Kuan Yew’s miracle. Malaysia signals... something else…

To get there, you cross the causeway into Johor. We left early, before 8am, to beat traffic. It took over 90 minutes just to cross the Second Link—and that’s the less busy causeway.

Within a kilometer of the customs checkpoint, we were stopped by police. We had to present our passports to confirm we weren’t locals. No apparent offense. But our savvy Malaysian driver knew the drill. Money changed hands. We continued.

The Ghost Town

We arrived at Forest City.

The development is a $100 billion bet that went wrong. China’s Country Garden built it for wealthy Chinese buyers seeking to move capital offshore. (Buy a flat in China, get a free one “near Singapore.”) The buyers never came. The towers stand largely empty.

The lobby of the Network School building was grand. Impressive in a slightly gaudy way—the aesthetic of Chinese capital optimized for brochures rather than residents. High ceilings. Gleaming surfaces. It felt like walking onto the set of Gattaca: beautiful, cold, impersonal.

There was hardly anyone there. No one to greet us. No one to help. This was the community that promised “your internet friends, coming from URL to IRL”—the Stanford 2.0 that would “take residential education to the next level.”

There were a few signs of life: individuals sipping coffee, staring at laptops. A sparse, gargantuan WeWork—but without the neon signs telling you to Do What You Love.

The book promised new countries. The school promised Stanford 2.0. What I found was a few people on laptops in an empty hotel lobby.

Two Flywheels

So what happened? How does a vision this interesting produce a reality this empty?

A charitable reading—and I think the more useful one—isn’t that Balaji sold out or lost his mind. It’s that he got captured by the wrong flywheel.

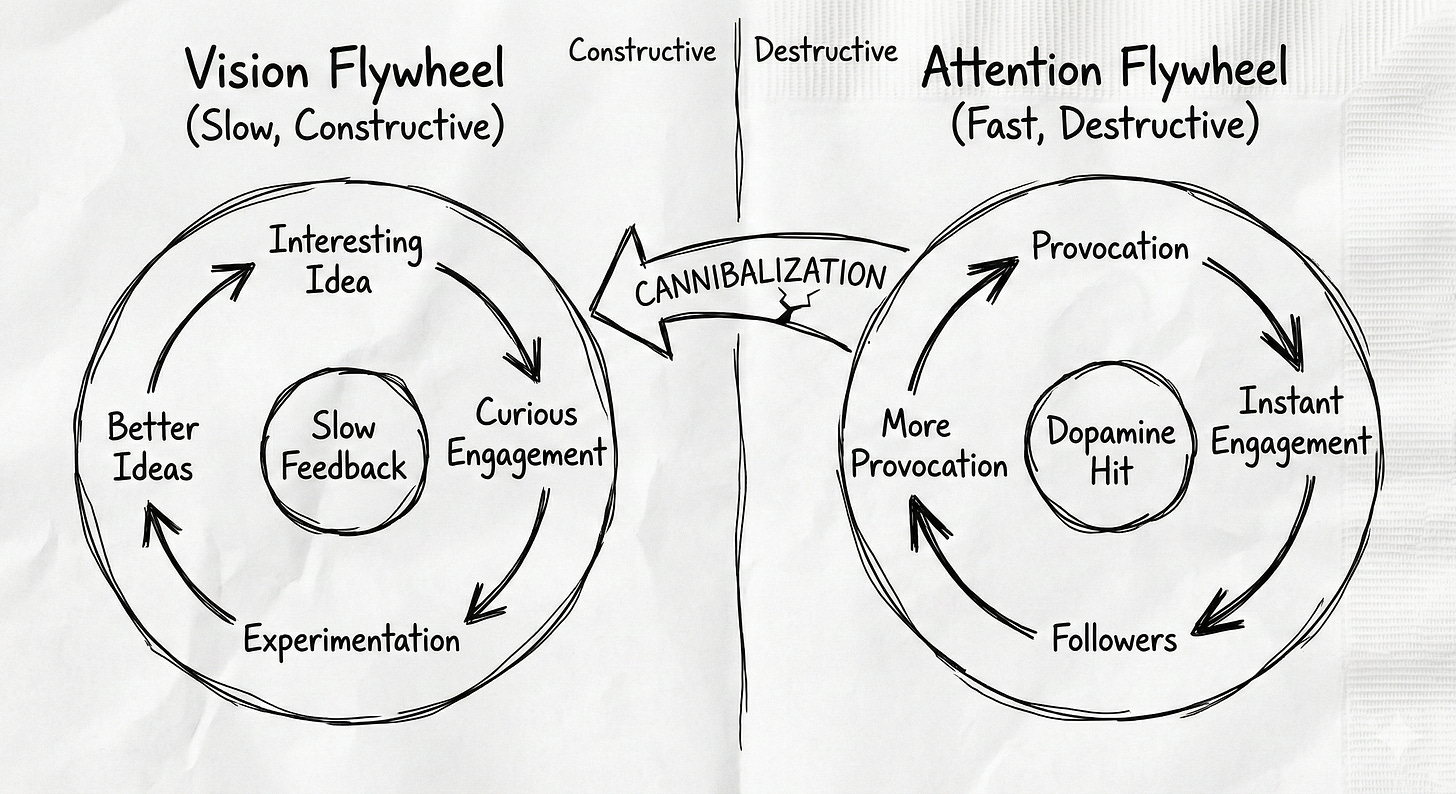

Every public intellectual runs two flywheels. There’s the vision flywheel: interesting idea → curious people engage → experimentation and debate → better ideas → more curious people. This one spins slowly, gives ambiguous feedback, and breaks easily. It’s the flywheel that produced the original Network State book.

Then there’s the attention flywheel: provocative take → engagement → followers → bigger platform → more provocative takes. This one spins fast, gives immediate dopamine, and is self-reinforcing. Every “No Blues” comment, every civilizational framing, every culture war take feeds it.

In a recent podcast with Benedict Evans, Balaji offered an inadvertently revealing analogy. He compared social media provocation to the Unabomber—who killed people to get an op-ed in the Washington Post. “He killed all those people for the distribution,” Balaji observed.

But the analogy cuts closer to home than he realizes. The Unabomber’s manifesto was read by millions. It didn’t start a movement. It started a manhunt. Distribution without the right community formation just gets you attention, not action.

Here’s the thing: when the attention flywheel spins faster than the vision flywheel, it doesn’t just compete for your time—it selects your audience. The people who show up for tribal provocation aren’t curious explorers who’d build pluralistic communities. They’re people who already agree. And once your audience is tribal conformists, you have to keep serving them tribal content or lose them. The attention flywheel cannibalizes the vision flywheel.

The irony is that Balaji understands this intellectually. In that same podcast, he quoted Chris Dixon’s “come for the tools, stay for the network“—a perfect description of how distribution should be baked into the product. But he didn’t apply it to his own most important project. The Network State’s “product” was pluralism, exploration, escape from political binaries. Its “distribution” was inflammatory Twitter provocation that attracted the opposite audience. Product and distribution pulling in opposite directions. No flywheel. A death spiral.

Compare this to Thread Reader, a product I know well because I run it. To unroll a thread, you reply “@threadreaderapp unroll” publicly. Everyone watching sees you use it. Usage is marketing. Product and distribution reinforce each other. The Network State needed its equivalent: participation in a community itself demonstrating the value to outsiders. Instead, Balaji built a product (Network School in Forest City) and a distribution channel (provocative Twitter persona) that had nothing to do with each other.

The ghost town in Forest City is what the vision flywheel produces when you’ve been feeding the attention flywheel instead. The provocative tweets got millions of impressions. The actual community got a few people on laptops in an empty hotel lobby.

The Road Not Taken

The tragedy is that someone is building what the Network State should have been.

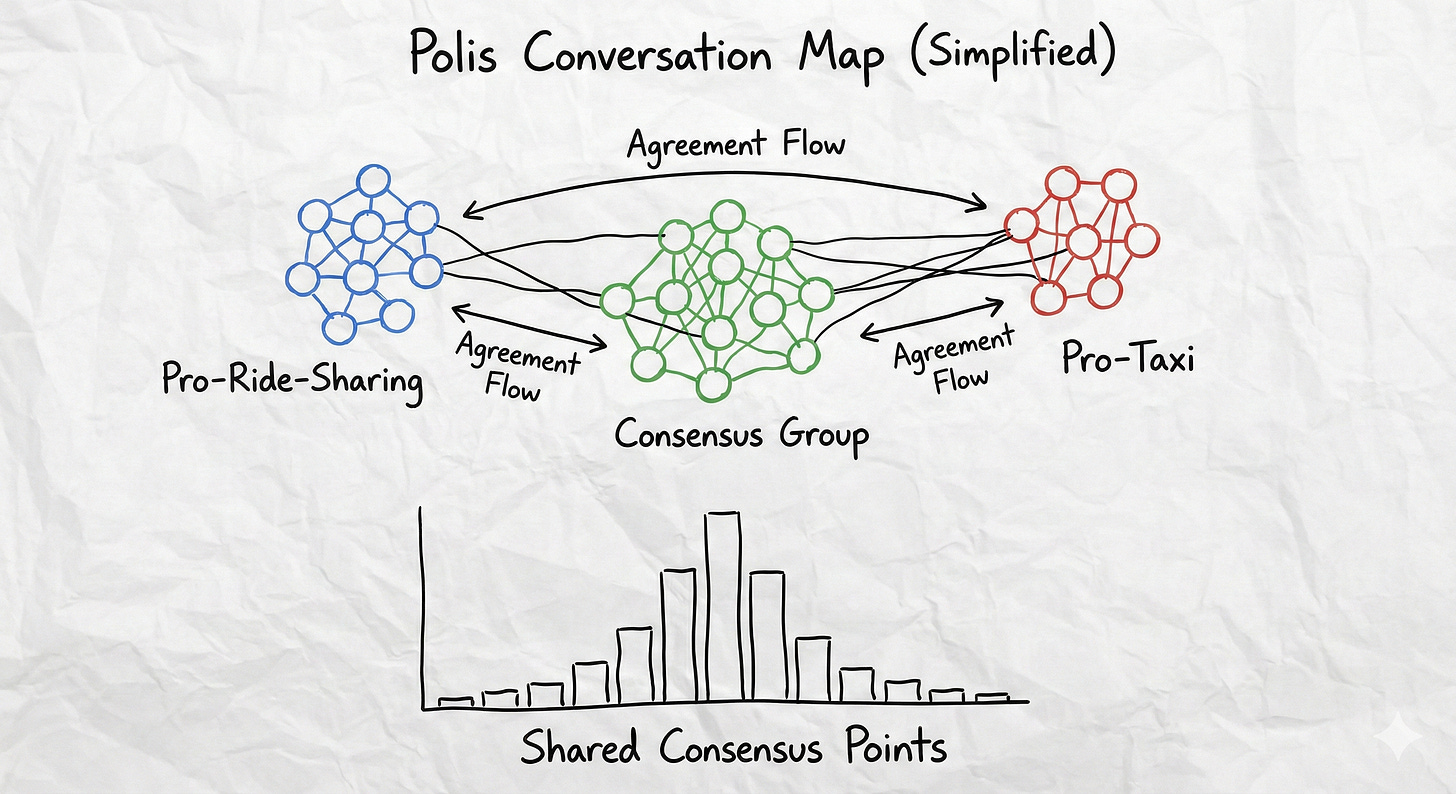

In 2015, Taiwan faced a familiar problem: Uber had entered the market, taxi drivers were furious, regulators were paralyzed, and online debate had devolved into two camps screaming past each other.

Instead, the civic tech community g0v (gov-zero) ran the dispute through vTaiwan, an open deliberation platform built on software called Polis. Over 4,000 citizens participated. Polis worked differently from social media: you could post opinions and vote on others’ statements, but you couldn’t reply. No threads, no dunking, no pile-ons. The platform visualized clusters of agreement and surfaced statements that drew support across opposing camps.

Something unexpected happened. As pro-Uber and pro-taxi groups competed for broader support, they started posting statements everyone could agree on—rider safety, liability insurance, fair competition. The divide between the two camps dissolved into a set of seven consensus principles. Uber, the taxi association, and multiple government ministries all signed on. New regulations followed.

This is what digital coordination looks like when distribution is baked into the product. Participation in vTaiwan itself produces the outcome—consensus that the government acts on. Each successful deliberation attracts more participants to the next one. Over 80 percent have led to government action. The flywheel is self-consistent. No provocative tweets required.

The contrast is stark. Balaji’s vision is exit: leave the broken system, build your own. Taiwan’s is voice: use technology to make existing systems more responsive. Balaji’s implementation narrowed toward conformity. Taiwan’s expanded toward inclusion. The US founders could have written “you must support the Jay Treaty.” They didn’t. They wrote principles that let supporters and opponents both participate. That’s the difference between a constitution and a manifesto—and the Network School chose manifesto.

What Taiwan’s experiment understands is that the interesting move isn’t exit. It’s pluralization. Not one network state with one commandment, but overlapping networks that prevent any single identity from dominating. That’s the architecture that could actually change something.

Boring Partisan Dumbasses

I feel some sadness writing this.

The Balaji who wrote The Network State in 2022—for all the book’s flaws—was trying something. He was asking interesting questions. He acknowledged my critique and said he was addressing it. I believed him.

And the exploratory Balaji is still in there. Listen to him in a same podcast with Benedict Evans—riffing on how block space is to crypto what bandwidth was to the early web, connecting Chinese flying cars to the smartphone supply chain dividend. When he’s thinking out loud rather than performing for an audience, he’s still one of the most interesting minds in tech.

But the attention flywheel demands to be fed. And it demands a particular kind of food.

Boring. That’s the word.

The Network State promised an escape from the tired left-right binary. What it delivered is predictable tribal reaction—you can guess the take before it’s posted.

The tragedy isn’t that Balaji became wrong. It’s that he — and his products — became boring. “Bitcoin succeeds the Fed, AI beats any Delaware magistrate” is a take you can get from a hundred other accounts. There’s no delta. The curiosity that made him worth following got swallowed by the culture war. The spirit of inquiry gave way to catechism. The questions became answers. The “what if?” became “you must believe.”

A Network State should be a protocol — a set of rules for interaction that anyone can build on. Balaji turned it into a platform — a set of content requirements you must subscribe to. A protocol is designed to be resilient to bad actors; a platform is designed to ban them. Network School feels like a digital skeuomorph of 20th-century tribalism: 21st-century tools used to rebuild 1950s-style ideological enclaves.

The attention flywheel won. The vision flywheel stalled. And a sparse WeWork in a Malaysian ghost town is all that’s left of the original dream.

What I Still Believe

I still believe something like the Network State vision could matter.

But the implementation has to match the vision. You can’t promise plurality and deliver conformity. You can’t promise transcendence of political binaries and deliver “exclude all Democrats.”

And you can’t build the future by feeding the wrong flywheel. Distribution has to be baked into the product—not bolted on as provocation.

The people actually building toward plurality—Taiwan’s civic tech community, the RadicalxChange movement, various experiments in digital democracy—are doing the quiet work that the Network State book gestured at but never completed. Their follower counts are smaller. But their flywheels are self-consistent.

Clayton Christensen would recognize the pattern. The disruptor never looks impressive at first—slower, less visible, serving a niche nobody glamorous cares about. Taiwan’s civic tech experiments won’t trend on Twitter. But they compound. The Network School could have been that kind of quiet disruption—start small, iterate, let the community grow from the bottom up, just as the 2022 book promised. Instead it followed the Country Garden playbook: build the grand vision first, assume the people will come.

“Good feedback,” Balaji wrote me in 2022. “Addressing most of that in the v2.”

I’m still waiting for the v2.

It's always a bit of a let-down to see enough promise in something that we put time and energy into providing feedback for its improvement, but the suggestions don't get implemented. Still, it's worth the effort. You never know when your participation in someone else's process is going to make a big difference and create that sense of triumph with both parties benefitting. It speaks to your character that you offered your perspective.